Change by Chance? How International Norms Travel Between the United Nations and the African Union

Kseniya Oksamytna

Lecturer in International Politics, City University of London

Nina Wilén

Director of the Africa Programme at the Egmont Royal Institute for International Relations

Associate Professor in International Relations, Lund University

23 November 2022 | #22.16 | The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and may not reflect those of UNU-CRIS.

In October 2022, members of the United Nations (UN) Security Council and the African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council met in New York and reaffirmed the importance of protection of civilians in peace operations. While their shared commitment to this norm is evident, do the two organisations actually define and operationalise it in the same way?

The UN was the first international organisation to formalise the concept of protection of civilians in peace operations and currently has the most detailed and well-developed guidance. Meanwhile, regional organisations, including the AU, are developing their own frameworks on this issue. The AU’s protection of civilians concept differ slightly from the UN’s concept. The UN’s protection of civilians concept has three tiers (protection through political process, protection from physical violence, and a protective environment), while the AU draft concept has an additional fourth tier: rights-based protection. We argue that this difference has emerged due to an unintended process of incidental adaption.

Why do International Organisations Adopt and Adapt Norms?

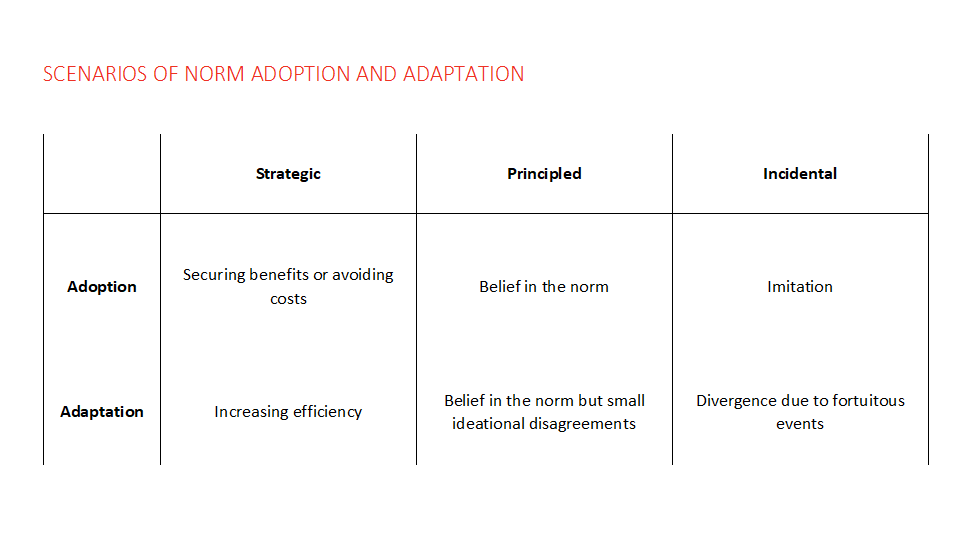

Global and regional organisations adopt norms for various reasons. It can occur strategically to acquire material or reputational benefits, for instance, related to external funding. They can also adopt a norm out of principle because they see it as appropriate for their own mission. Along the way, organisations may modify norms before or while integrating them to adapt them to their own institutional context. In the case of strategic adaptation, organisations make adjustments to maximise the advantages associated with norm-following or to avoid certain costs of wholesale adoption. In the case of principled adaptation, modification may occur when an organisation genuinely disagrees with some aspects of a norm while finding it appropriate overall.

The AU has engaged in both the adoption and adaptation of the UN’s approaches to the protection of civilians. This refers to proactive protection, or active efforts to shield civilians from violence, but also to preventive protection. The latter entails safeguards against peacekeepers harming civilians intentionally, for example, through sexual exploitation and abuse, a problem in both UN and AU peace operations, or unintentionally through collateral damage, a particular problem for the AU’s operation in Somalia.

In general, the AU strives towards convergence with the UN’s protection of civilians approaches because of the depth of the partnership between the two organisations in peacekeeping: when they draw on the same pool of troops, take over each other’s missions, or even run joint operations, peacekeepers on the ground should not be wondering what each organisation means by protection. In terms of preventive protection, the AU’s adoption of policies on conduct and discipline as well as prevention and response to sexual exploitation a few years after the UN adopted its policies, has been linked to the AU’s reliance on the UN’s financial support for its peace operations. The unlocking of UN funds thus provided an additional strategic reason for the AU to follow the UN’s approaches in this case, and the implementation of those AU’s policies is encouraged by both the UN and the EU. These examples are all cases of strategic adoption.

Yet, the AU is also conscious of the need to project its own identity in the field of peace operations to ensure institutional relevance and reflect the normative positions of its member states. This consciousness paves the way for norm adaptation.

The Rights-Based Tier in the AU’s Protection of Civilians Concept

The AU’s concept on proactive protection of civilians, though still in draft form as of 2022, features an important difference compared with the UN’s concept: the right-based protection tier. We argue that this is due to neither principled nor strategic reasons. Instead, it represents a third type, that is often overlooked: incidental adaptation, i.e. the result of unanticipated factors or events. Even if the AU had planned to adopt the UN’s concept fully, unintended developments got in the way, as one of our interviewees suggests:

“This discrepancy exists because when the UN first developed its guidance, it had the same four-tier approach. It was copied and pasted by the AU to say that they were pretty much on the same page as the UN, but then the discussions went separate ways…[I]n the UN, the decision was taken by [the Department of Peace Operations] to drop the rights-based approach because the entire concept is rights-based and all three tiers are rights-based. The rights-based approach was mainstreamed. The AU tried to do the same thing, but member states wondered: ‘Hang on, why do you want to take human rights out of the equation now?’ And the AU did not succeed in selling the narrative that the rights-based approach is mainstreamed.”

At the UN, human rights were ‘mainstreamed’ (i.e., integrated across all tiers of the protection of civilians concept) because they were the ‘turf’ of UN agencies rather than peacekeeping missions. The AU did not face similar institutional constraints that would have prevented it from keeping the rights-based tier in the protection of civilians concept. This combination of circumstances resulted in differences between the UN’s and the AU’s concepts. What may appear like purposeful adaptation is the result of norm evolution in their original context, while its original version had already travelled to the African Union.

Expanding the Research Agenda on Inter-Organisational Norm Diffusion

Future research could explore varieties of inter-organisational norm adoption and adaptation beyond UN-AU relations. For example, the European Union’s (EU) concept of protection of civilians does not have tiers but four principles: harm mitigation through a proactive posture, comprehensive engagement with all actors, contribution to protective environment, and conflict sensitivity. Meanwhile, the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation’s (NATO) conceptual framework on protection of civilians includes mitigating harm to civilians during operations, protection from physical violence, cooperation with human rights-focused local actors, and coordination within the international community. Reasons for the similarities and differences not only between the UN’s and the AU’s concepts of protection of civilians but also between the UN’s, the AU’s, the EU’s, and NATO’s concepts need to be examined not only in terms of strategic and principled adoption and adaptation, but also factor in unintended consequences.

Each international organisation draws on its own mandate, priorities, and experiences in defining its approach to protection of civilians but does so in a global environment, where influences of other organisations are often significant. Exploring the microprocesses of inter-organisational exchanges that lead to specific outcomes is important for both scholarship and practice. The unintended consequences of a fortuitous sequence of events have only received limited attention in the academic literature so far. This novel concept of incidental adaptation constitutes a missing element and encourages a deeper appreciation of the role of chance in international affairs.