Is Lockdown the Same, Everywhere, For Everyone?

Rossella Marino

PhD Fellow, UNU-CRIS

4 May 2020 | #20.18 | The views expressed in this post are those of the author and may not reflect those of UNU-CRIS.

It took a while before the international community fully realised the sweeping gravity of the Coronavirus pandemic - proclaimed by the World Health Organization on 11 March. As the first people tested positive for Covid-19 in Europe, experts, politicians and the media were divided, at best, on the actual seriousness of this unknown disease. In the North of Italy – which became one of the global epicentres of the pandemic – portions of the political and economic sectors were initially downplaying the danger of the quick diffusion of COVID-19 and encouraging people to go on with their lives, interacting, exchanging, moving as usual. Unfortunately, this is the perfect situation for a virus to spread. Soon enough, COVID-19 was in fact producing mild symptoms in a majority of infected people, but the substantial number of those who developed serious respiratory complications gradually overwhelmed many countries’ health systems. In the absence of a cure or vaccine against this unfamiliar disease, these countries resorted to lockdown and social distancing measures aimed at reducing interpersonal contact to an essential minimum. In this context, people are generally allowed to go out to purchase necessities or reach workplaces, provided their jobs fall in the list of government-identified essential occupations. Bringing socioeconomic systems to a sudden halt immediately affected productive sectors, as well as the vulnerable strata of populations, namely those who cannot rely on stable incomes or salubrious accommodation. In the Global North, affluent countries are attempting to support these groups through increased public spending. As the effectiveness of these support attempts remains to be seen, attention should be also paid to what less privileged countries can do to counter the disruptive and unexpected Coronavirus wave.

The Gambia is the smallest country on mainland Africa, encircled by Senegal and overlooking the Atlantic Ocean. A quick look at official statistics and mainstream rankings reveals the country’s dire socio-economic condition - in terms of GDP by country, Gambia ranked 182nd in 2018. As for the more comprehensive indicator of the Human Capital Index – measuring the expected individual productivity based on the quality of national education and health – The Gambia scored 0.40 in the same year, against Sweden’s 0.80, to pick just one high income country. These sorting systems aside, the endemic difficulties of this former British colony, independent since 1965, are plain to see for any visitor who is not directly headed for the luxurious tourist sites of the coast. The densely populated urban areas around the capital and the sea cost appear as extremely lively and buoyant centres for small trading and (polluting) car transport – alongside the proliferating banking and communication service providers. These areas are often the springboard for the perilous emigration route to the North which so many young and capable Gambians take, despite the well-known risk of death or imprisonment, because of their feeling of not having enough opportunities for (economic) improvement where they were born. For those who remain and do not benefit from the help coming from the few who successfully made it abroad, the street commerce of local products, second-hand items and imported goods, as well as the interaction with Caucasian tourists – viewed as pots of gold or living travel documents for the West – often constitute the first and most immediate means of subsistence. This picture intermingles with the (still) generalised enthusiasm for the deep political change occurred in 2017, which brought a population used to suffering from the prevarication of authoritarianism to enjoy all the basic democratic freedoms.

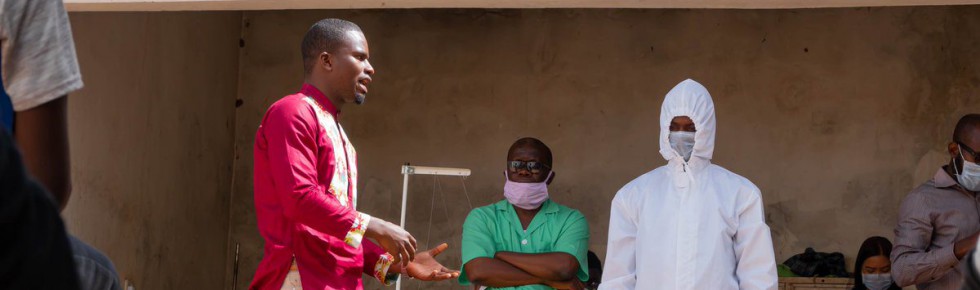

The first confirmed case of COVID-19 in the so-called smiling coast of Africa, imported from the UK, was registered on 17 March. Those were the days in which the European Union was shutting its borders and all prominent international airlines were putting their operations on hold. The numerous tourists and foreigners then present in The Gambia hastily took the last planes available to return to their comfortable Northern homes in these trying times. Since then, the warm and spacious beaches caressed by the water of the Atlantic Ocean have been deprived of their largely European customers, who usually engage in volatile relationships with their Gambian temporary friends, tour guides and, occasionally, intimate companions. To date, the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases in The Gambia is ten. Yet, despite the limited degree of contagion with respect to other global regions, anti-COVID-19 measures have also been implemented by the consolidating Gambian democratic establishment. On top of the screening actions initially carried out at the Banjul International Airport, the head of government, Adama Barrow, publicised via Facebook his decision to enforce a nationwide state of public emergency in late March. This entailed the closure of non-essential outlets and public places as well as places of worship. Earlier on, travel restrictions had been imposed next to the shutting down of schools and universities.

As outlined above, in the current absence of a vaccine, social distancing measures are potentially the only shield we globally have against the galloping COVID-19 virus. Yet, these measures have profoundly different effects based on the context in which they are applied. Socio-economic systems of a largely informal nature which depend exclusively upon close social interaction and, as in the Gambian case, post-colonial touristic structures – even if endowed with some safety nets – will be hit the hardest. Beyond the financial side, the case of The Gambia also shows how politically sensitive these emergency protective measures are. As Adama Barrow became the first democratically elected leader of the country in decades, the quarrel around the length of his mandate produced much unrest among the population, resolved not to slip back into old customs. Although a new Constitution was recently approved which has been met with moderate favour, the attribution of exceptional powers to the executive in young democracies gives rise to preoccupation. This thorny scenario will inevitably result in a stronger emigration drive, in defiance of the deterrence actions normally put in place by receiving countries, which are, if possible, even more indifferent towards migrants in these difficult times. Therefore, as prominent international organisations are already warning the public on the extreme livelihood consequences of the pandemic on Africa, one of the questions to tackle in the post-emergency phase will be how to address these new causes of vulnerability, both at the national and international level.

More on COVID-19 in the Connecting Ideas series:

East Asia and Pacific: Countries Must Act Now to Mitigate Economic Shock of COVID-19

COVID-19 (Coronavirus) Drives Sub-Saharan Africa Toward First Recession in 25 Years

COVID-19: An Opportunity for Regional Cooperation in Latin America?

The Irresistible Rise of Health Diplomacy: Why Narratives Matter in the Time of COVID-19

Trade Policy and the Fight Against the Coronavirus

When China Sneezes, Asia Catches a Cold

Yes, Crises Do Happen: A Plea for Feeling More Vulnerable After COVID-19

What Can the Coronavirus Teach Us About Regional Integration in Health?