COVID-19 in Pakistan: Reality Presents Opportunities

Zoha Anjum

Master of Public Health (MPH), McMaster University, Canada

LinkedIn: www.linkedin.com/in/zoha-anjum

Ayak Wel

Master of Arts in Globalization Studies (MA), McMaster University, Canada

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/ayak-wel/

16 July 2020 | #20.27 | The views expressed in this post are those of the author and may not reflect those of UNU-CRIS.

The novel coronavirus has severely impacted global systems. While Italy, Spain, China and other countries are on their way to recover from COVID-19, countries like Pakistan have now started to see a surge in their number of COVID-19 cases. This piece explores the current COVID-19 situation in Pakistan and elaborates on the needed healthcare and public health reforms, while reiterating the importance of regional collaboration in tackling this crisis.

Background

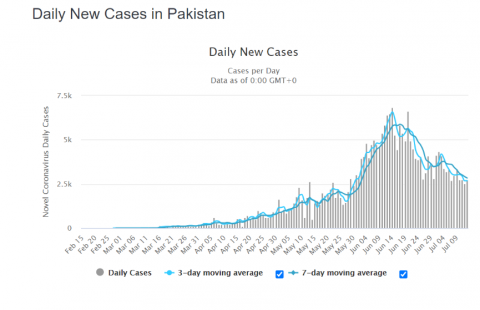

Pakistan reported its first two cases of COVID-19 on February 27th, 2020. The cases did not increase significantly at the beginning of the pandemic as a nationwide lockdown was quickly imposed. However, over the past few weeks, Pakistan has been seeing thousands of new cases every day. Estimates show that the actual burden of COVID-19 in Pakistan may be even worse as only symptomatic individuals tend to get tested. Additionally, Pakistan is only completing 50% or less of the World Health Organization’s (WHO) recommended 50,000 COVID-19 tests per day.

Healthcare systems in Pakistan may also be on the verge of collapse. Nationally, there are only six hospital beds available per 10,000 individuals in the population, which presents ethical dilemmas on how those beds will be assigned to patients with diseases other than COVID-19. Moreover, the COVID-19 caseload is disproportionately higher in urban areas since many people travel to cities for better access to healthcare, and thus, spread the virus to others on their way.

Current Situation in Pakistan

The recent surge of COVID-19 cases may be a result of lifting the lockdown around Eid-al-Fitr, a celebratory event marking the end of the holy month of Ramadan for Muslims. Since Eid-al-Fitr, the cases have been increasing at an exponential rate. Unfortunately, Pakistan does not have adequate public health (testing, tracing and isolating) and healthcare (medication, ventilators and hospital beds) resources and interventions in place to prevent the coronavirus spread. Therefore, the WHO recommended urgent, intermittent, two-week long cycles of lockdowns as they feared the cases could reach up to 800,000 by the end of July.

Following the WHO recommendations, many cities (e.g., Lahore and Karachi) in Pakistan implemented a partial lockdown to control the spread of COVID-19 in early June. In a partial lockdown, only the communities with high COVID-19 caseload are under a complete lockdown. Police have been appointed at the lockdown entry and exit points to stop travel between communities. Furthermore, only one person from each household is permitted to go outside at a time. All shopping malls, public transit and offices have been closed in the areas under lockdown. Since the partial lockdown was imposed, the number of cases has decreased along with the daily number of tests conducted. Therefore, this downward trend must be interpreted with caution.

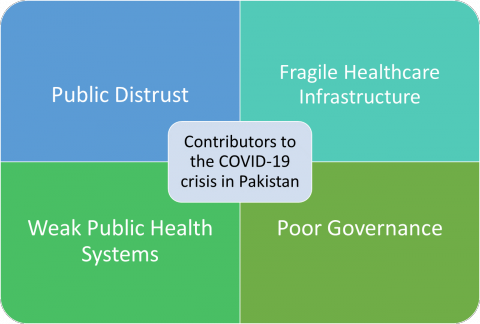

Contributors to the COVID-19 crisis in Pakistan

Public distrust has been one of the major contributors to the skyrocketing cases of COVID-19 in Pakistan. Misinformation and rumours spread faster than the coronavirus itself, and this has led to supply hoarding and non-compliance with public health interventions. Many individuals even refused to acknowledge that coronavirus exists; they chose to believe the conspiracy theories as they continued to live their everyday life and gather in large crowds. There have also been reported cases of violence against healthcare workers, where some relatives of the patients claimed that coronavirus is not real, and the doctors are just killing patients with ‘poisonous injections’.

While COVID-19 has impacted the global economy, low-and-middle income countries disproportionately face worse outcomes. In Pakistan, for instance, COVID-19 may push millions of individuals into unemployment, and consequently, poverty. Estimates show that poverty headcount may increase by 4.7%, and up to 9.2% in the worst-case scenario. The Pakistani prime minister, Imran Khan, has been hesitant about imposing extended lockdowns since it will impact the daily wage earners and uninsured and migrant workers the most.

Opportunities for an integrated response

Despite the ongoing challenges, Pakistan’s government was quick in establishing a National Action Plan to curb the impact of COVID-19. While the action plan aims to ensure the containment of the coronavirus in a timely manner, much more work is needed to combat this relentless pandemic and its long-term effects. Evidence points to weaknesses in Pakistan’s healthcare system, including challenges in establishing health infrastructure, formulating health policies, inadequate public-private partnerships, and limitations in rural healthcare provision – all of which are linked to poor governance and continue to exacerbate COVID-19 outcomes. This pandemic should be a wake-up call for Pakistan, considering that the human, social, and economic costs of poor healthcare systems and inadequate public health interventions will be catastrophic.

Indeed, there is an urgent need for a unified strategy in tackling the pandemic at the national level, including healthcare reform, stronger public health interventions, and better coordination between public and private sectors. Pakistan may consider focusing on providing adequate beds, medical equipment, and professionally trained personnel. Adapting robust health policies and creating a strong health infrastructure that make healthcare accessible for all citizens is an important and timely investment.

Currently, Pakistan has the laboratory capacity to conduct over 46,000 COVID-19 tests per day, yet administers around 20,000 tests each day. Strengthening Pakistan’s public health service delivery requires sufficient training and infrastructure that can enhance the country’s ability to test, trace, and isolate cases of COVID-19. The resources required to implement these reforms are beyond the scope of the public sector alone and can arguably lead to significant financial gaps. Private and non-state sectors could help bridge these gaps by mobilizing financial resources and technical capabilities, leveraging the efforts of the government. Private sectors in Pakistan have previously worked to bridge weaknesses in healthcare provisions, despite being unregulated due to lack of state enforcements. In the COVID-19 era, investing in these reforms is not unachievable in Pakistan, and will create a system that is effective in identifying, preparing, and responding to public health emergencies in the country.

The first two COVID-19 cases in Pakistan were pilgrims returning from Iran. We live in an integrated world and any failure to contain COVID-19 in one country could endanger the safety of others. This weakest link hypothesis calls for an interlinked response across regions. Similarly, efforts of regional bodies would undoubtedly provide important lessons that could lead to augmented cross-country collaboration to recover from this crisis. While one can acknowledge the complex security situation in Pakistan and its surrounding areas, the crisis brought on by COVID-19 should be an opportunity for more regional integration for mitigating its spread. This is especially critical because infectious diseases such as COVID-19 do not know borders and affect people transnationally. Organizations such as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations - Regional Forum (ASEAN-ARF), of which Pakistan is a member, have an important role in facilitating a regionally-joint response. One of the main objectives of ASEAN-ARF is to foster dialogue on critical security issues in the region and to promote peace. More than ever, now is the opportunity for ASEAN-ARF to take center stage in nurturing diplomacy and peacebuilding in the region because when the region is stable, governments will emerge from this crisis stronger, and be better equipped to tackle COVID-19 and future pandemics together.