Transaqua, Lake Chad and the Congo Basin – A Call for Cautious Action

Nidhi Nagabhatla

CoDirector, Water Without Borders Programme

Principal Researcher: Water Security, United Nations University - Institute for Water, Environment, and Health

Ramazan Caner Sayan

Postdoctoral Fellow: Water Security, United Nations University - Institute for Water, Environment, and Health

This blog is based on the paper Soft Power, Discourse Coalitions, and the Proposed Interbasin Water Transfer Between Lake Chad and the Congo River.

30 October 2020 | #20.31 | The views expressed in this post are those of the author and may not reflect those of UNU-CRIS.

Transaqua, the massive water infrastructure project first pitched in the 1970s, is back on the political agenda and claims it can reshape regional politics in Central Africa. The USD 50 billion plan calls for the construction of a 2,400-kilometer canal to divert water from the Congo River Basin and replenish Lake Chad. The construction works will take place in the Central African Republic and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), not in the riparian states of the Lake Chad Basin.

Discussion re-emerged in the mid-2010s, when state-owned PowerChina offered to support this infrastructure investment. PowerChina signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the Lake Chad Basin Commission (LCBC) in 2016, followed by an MOU between PowerChina and Bonifica in 2017 to collaborate on the water transfer proposal. Bonifica has been promoting the project since the 1970s. LCBC endorsed the Transaqua project as a preferred option of water transfer to save Lake Chad after the International Conference on Lake Chad (2018). An MOU was signed with Italy for cooperation towards implementation.

Geopolitical stability and human security are global issues. In past decades the Lake Chad region saw a severe water crisis and endured one of the most turbulent times in its political history. More than 17 million people in the region face a multitude of difficult crises related to extreme poverty, water stress settings, climate change and conflict. Half of this count is in need of support, protection and humanitarian help, as noted by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) last year.

A closer look at the declarations and official documents promoting Transaqua reveals multiple narratives outlining ambitious targets and claims of future benefits to both basins, as well as promises to resolve significant political, economic, and even regional insecurity challenges, including the Boko Haram threat and out-migration.

The DRC is the only major actor raising concerns about Transaqua. Note that DRC is expected to host most of the construction work and allocate water from its territories. The socio-economic, cultural and ecological damage projected in the Congo Basin, the potential political problems on water allocation among Congo Basin countries, and the lack of active participation of riparian countries of the Congo Basin in the Transaqua-related decision-making are facets of considerable concern.

What generally does not feature in Transaqua debates are:

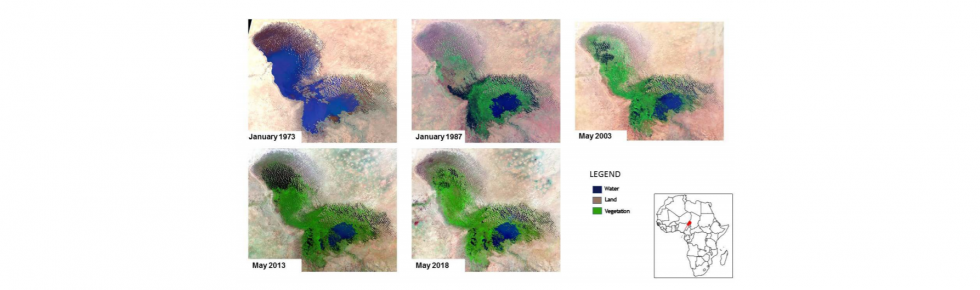

- The historical change of Lake Chad's water levels. Why did the Lake go dry? Was it a natural phenomenon, was it due to pressure from human activities or possibly a mix of both?

- Future scenarios. Will filling the Lake again guarantee its water security for the short or long term?

- How will this project impact local and pastoral communities’ cultural and customary norm?

These glaring narrative gaps raise some thorny questions. To what extent and in what direction are corporate players like Bonifica and PowerChina influencing water relations, allocation and sharing, and transfer arrangements? To what extent are these and other private actors influencing the water future of Central Africa and the Sahel region? Interested readers can learn more about the ongoing discourse in our paper. We have attempted to explain how private interests are shaping hydro diplomacy of the transboundary waters in the world's two most controversial basins: Lake Chad and the Congo.

Transaqua is still in the feasibility stage. Key players such as the World Bank, CICOS (the river basin organization managing the Congo River), environmental NGOs like International Rivers, and riparian states of the Congo River (except the DRC) have not disclosed their position on Transaqua. Their involvement or opposition to this project will define hydro diplomacy in the region. Despite all the political momentum gained in 50 years, the diverse notions of Transaqua point to no clear agreement towards successful implementation.

In recent years, the proposal is more in the limelight as a remedy for mitigating both humanitarian and economic concerns. However, the need for an in-depth look into the geopolitical power structures, community voices, and perspectives of all stakeholder needs persists. So, it is vital to recognise what this proposal/project stands for; how its objective represents stakeholders, beliefs, and opinions.

When water is a business proposal, negotiations need to reflect the stakes and interests of all parties and communities sharing the basin resources. One could argue that social and cultural arrangements are “stakes and interests” in such discussions. And, if the project is to be implemented, the trade-offs need to be assessed cautiously. Decision-makers should be careful not to use only dimensions such as economic criteria and corporate profitability to assess the feasibility of the water infrastructures.

Transaqua supposedly is the biggest water project in the world. One of the claims reads that the waterway could irrigate between 50 to 70 thousand kilometres in the Sahel, a territory spread in eight countries. And ten countries in the region would be beneficiaries of the transport system, along with the promise of generations of hydropower for all. But how can it all start when DRC, the land with the largest share of the Congo river basin spread, has a profound apprehension of the proposal? The COVID situation and the response measures highlight the unmet water needs of communities and populations. In the DRC, three-quarters of the population has no access to safe drinking water (UNEP, 2011). Can the country afford to discuss water-sharing dealings without resolving its domestic water management issues? Maybe so, however, the DRC's voice and opinion on Transaqua is still either limited or totally discounted.

Transaqua points to crucial opportunities and lays out ambitious objectives in its plan. Nonetheless, it remains to be seen if this proposal turns the tide with its ambitious agenda, as the lack of participation and consensus-building remains as a blaring gap in its planning process.

In our paper, we analyse the project’s multiple stakeholders and their reasons to support or criticize it. What we found is that there seems to be no evidence of any strategy that aims to bring together various actors and agencies to help strengthen their voice and involvement and build consensus. We hope you will find some of the insights outlined in this paper informative. The long-term future of Transaqua will largely depend on a collective regional plan and on the integration of concerns from communities and stakeholders across both basins.