Camus, Revolt and Europe

04 December 2019

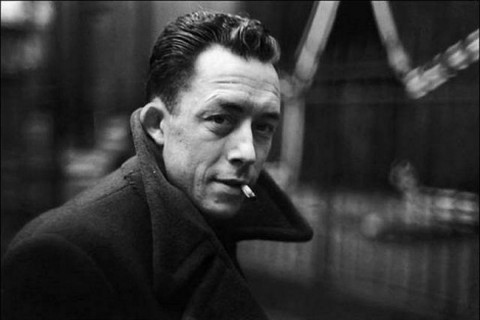

In 1951, the French-Algerian philosopher Albert Camus published L’Homme Revolté (The Rebel), the most political of his essays and perhaps the most comprehensive recapitulation of Camus’ intellectual journey. A few weeks from the anniversary of his birth, it is worth recalling what this seminal work can still teach us about conflict, history and the future of cooperation among men and nations.

Erudite yet articulate, and not without a hint of lyricism, the essay is a philosophical anthology, littered with biblical and historical references, of man’s rebellion from the dawn of the French Revolution to the tragic events of the twentieth century, epitomised by the rise of totalitarianism.

In the book, Camus declines rebellion in all its aspects, from philosophy to history, to art and poetry, but it is the historical account of revolt that bodes the greatest implications at the societal and political level. While the 1789 French Revolution sanctioned the liberation of peoples from the tyranny of absolute monarchies through the beheading of Louis XVI and globally accelerated the rise of republics and democracies, the divinity of God, embodied by the King, was soon substituted with the undisputable divinity of reason, justice and virtue. Since, as the royal power before, these notions could not be questioned, the revolution inevitably escalated to the Terror of Jacobinism. The regicides and deicides of the revolution were then substituted by Hegelian idealism, arguably the most influential philosophy of the 19th century, with its vision of history as “perpetual strife and struggle of wills bent on seizing power”. In Camus’ accounts, it is precisely Hegelian absolute idealism, coupled with the influence of nihilism present in subsequent philosophers like Nietzsche, that became a driving force for the affirmation of totalitarian regimes, both Fascist and Communists, on the eve of the Second World War.

Yet, as bleak and hopeless as this account might seem, the book’s last chapters offer a glimpse of the future of Europe which brims with hope and which in some respect pioneered modern-day European integration.

Thought at the Meridian

As it stands clear from the historical trajectory he traces, Camus depicts excess as a force that underpinned the revolutions on European soil until the first half of 20th century, with all the blood-shedding that ensued. That is why in the penultimate chapter of his essay, he counterposes the mass dimension of revolution, which invariably leads to terror, with the individual dimension of rebellion. Rebellion, in particular, must be rooted in what Camus labels la pensée mediterranée (Thought at the Meridian): through this vivid, lyrical metaphor, he represents the perpetual struggle of man to balance his excesses into an equilibrium which encompasses empathy and understanding through human connection. While rebellion evokes images of violence and turmoil in people’s minds, Camus makes it coincide with moderation. Indeed, in a century in which blind violence, intolerance and chauvinism had been the rule, a call to moderation, equilibrium and reconciliation was the most rebel of gestures. In this sense, as it is observed in a comment by Robert Zaretsky, what drives rebellion is moral action and decency.

Rebellion is also key to inform about how European cooperation came about in the aftermath of the Second World War; as Camus remarks, “it is those who rebel, at the appropriate moment, against history who advanced its interests.” In a way, the founding of the European Coal and Steel Community has represented precisely that: a rebellion against history. In an extraordinary feat of idealism, after centuries of rivalries, violence and war which ultimately culminated in the ravages of genocide and totalitarianism, six European statesmen decided they would do anything they could to ensure that war would no longer be Europe’s destiny. Cooperation became the instrument of rebellion against past decades of secret diplomacy and balance of power politics. In this sense, rebellion is the positive element of its negative counterpart, the absurd (a concept comprehensively developed in Camus’ previous works The Outsider and The Myth of Sisyphus).

The Mediterranean spirit of which Camus was a herald has subsequently been defined as a sort of “equilibrium under the sun”. The cooperative response that Camus opposes to the absurdity of life is the same answer that the international community ought to seek against the seeming unpredictability of the international order. In this perspective, while international cooperation may not always be immediately profitable, it is the only way we know to curb the forces of self-interest which tend to pit one nation against the other.

Coming Apart

Despite this, today’s trend seems to revolve around nationalism and a return to borders. In other words, towards disintegration. In both Europe and other parts of the world, governments are reverting their attention to the preservation of their national identities against potential threats, building walls and erecting fences. They seek to dismantle the liberal world order that emerged after the Second World War.

Although harnessing the contradictions and inequalities enshrined in the current political order can be seen as legitimate, these disintegration actors are not presenting any viable alternative which can combine national identity with a true global ethos. On the contrary, they are fuelling distrust and preaching beggar-thy-neighbour solutions to common problems. Against this background, Europe might not necessarily be on the edge of a precipice, as French President Emmanuel Macron’s apocalyptic vision of Europe’s geopolitical predicament foretells, however it is a fact that regional and international cooperation is currently waning. Europe still has a potential to reverse this trend, but it will have to do so with haste.

In this perspective, Camus’ vision of Europe lets us remember that the continent “rebelled” once against its faith, and that it should rebel once more: in an interview, he declared “unity and diversity, and never one without the other, isn’t it the very formula of our Europe?”, and continued “I don’t believe in a Europe abandoned to its own differences, that is abandoned to an anarchy of rival nationalisms”.

Camus’ insights for the world’s current struggles can also be found in his reflection on language: as a reaction to the atrocities of the War and to the chauvinist rhetoric that had inflamed them, Camus made back in 1951 an explicit call for moderation, humanity, and clarity of language.

At a time in which tones are so inflated - whether it be the harsh rhetoric of Donald Trump, the hard tones of the Brexit drama or the shouts of populism all around Europe - coming back to Camus’ teachings and reflections on the nexus between language and action can help contemporaries to conclude how extreme language can exacerbate moods and influence political events.

To conclude, we are now living in a phase of tectonic shifts in multiple domains. These will affect every part of the world, and Europe will be no exception. The EU may not be able to overcome history, but it must try to tame the forces that produce tension and separation. Once more, it must achieve a rebellion against extremisms, founded on moderation and equilibrium. In such a dire conjuncture, Camus’ idealism and lyrical impetus can still teach us something.

Filippo Blancato is a Research Intern at UNU-CRIS, and recipient of the UNU-CRIS Best Thesis Award at the College of Europe in 2019.

Contact: fblancato@cris.unu.edu