RIKS: A Forthcoming Structured Introduction to the Regional Bowls of Spaghetti

Zane Šime

Research Intern, UNU-CRIS

23 April 2020 | #20.13 | The views expressed in this post are those of the author and may not reflect those of UNU-CRIS.

25 years ago, Jagdish Bhagwati came up with the ‘spaghetti bowl’ phenomenon, sometimes referred to as the ‘noodle bowl’ and ‘needle bowl’. As Richard Stubbs and Jennifer Mustapha sum up, “the term refers to the different tariff regimes, rules of origin, and so forth that govern” free trade agreements “and which create criss-crossing linkages that look like noodles in a bowl. The seemingly negative aspects of this development raise two important questions.” First, is it possible to systematise these scattered economic linkages? Second, are transnational institutions and regional arrangements well-equipped to promote the welfare and economic growth of a certain geographic area in a coherent manner?

Over the years, the term has found plenty of enthusiastic users well beyond the circles of trade analysts. For example, the article “The European Union’s two dimensions: The Eastern and the Northern” written by Christopher S. Browning and Pertti Joenniemi, refers to the Northern Dimension as an initiative unleashing ‘a bowl of spaghetti’. The term hit the nail on the head. Thanks to the Northern Dimension and a number of other initiatives launched during the past 20 years, the Baltic Sea Region has evolved into space with dense and remarkably multi-faceted layering of collaborative structures, networks, platforms, and dialogues. One might say, a variable geometry par excellence. The continuous international topicality of the ‘spaghetti bowl’ term is demonstrated by the scholarly usage of it when referring to the challenges of dissecting the role of regional organisations in the integration processes, such as the Americas analysed by Gaspare M. Genna in the Fourth World Report on Regional Integration (2017).

For an outsider - meaning a person who is not in daily interaction with the elements of the multi-level governance - navigating between various regional formats might seem challenging. This is where the forthcoming Regional Integration Knowledge System (RIKS) platform will come in handy. With a concise listing of the main details about regional organisations and arrangements shaping the multilateral cooperation and its impacts on the daily lives of many people working and living across Northern Europe (and other parts of the world), RIKS will serve as a promising springboard for a deeper dive into the intricacies of multilateral consultations and collaboration.

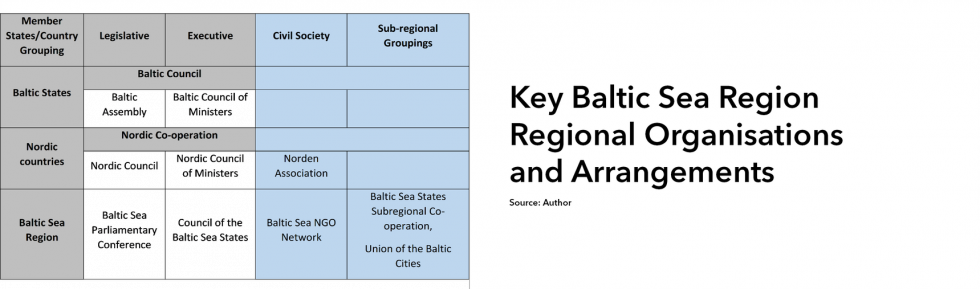

To provide a glimpse into what type of regional organisations and arrangements will be displayed on the platform, a simplified outline of the Baltic Sea Region is provided. It indicates key regional organisations operating in the Baltic Sea Region with attention paid to distinguishing between legislative and executive bodies, non-governmental section and sub-regional groupings. The overall focus of RIKS is on offering a concise guide to the regional organisations, with short explanations of the key structural elements of each of the organisations or arrangements, such as the separate formats convening the legislative and executive representatives of the corresponding member states. While RIKS does not entail an inventory of organisations assembled by the civil society and sub-regional groupings, which are outlined in light blue colour in the table, it aims to cover those subnational authorities which have displayed a capacity to establish highly institutionalised arrangements, and which are recognised as strategic partners by the major regional organisations.

This compact table leaves out many elements and initiatives which are blurring the lines between the listed clear-cut arrangements and the territorial units they cover. Just to name one example, the table does not feature the Nordic-Baltic Cooperation (NB8). It is a “regional cooperation format which as of 1992 has brought together five Nordic countries and three Baltic countries (Finland, Sweden, Norway, Iceland, Denmark, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania) to discuss important regional and international issues in an informal atmosphere” and is currently chaired by Estonia. This is not the sole variation of ‘NB’ meetings. These regional intricacies are not depicted in RIKS. Purposefully, RIKS is designed to offer an introduction to the key and relatively highly institutionalised regional organisations. It is not an exhaustive data base aimed at listing all multilateral formats that have been put in place in various parts of the world.

Coming back to Gaspare M. Genna’s findings about the Americas, the uncertainty related to the impact of a specific multilateral agreement over another deserves more attention: “Given multiple memberships, it would be difficult to disentangle to say if integration due to the MERCOSUR agreements had any more or less of an impact than say trade with the associate members of MERCOSUR (through FTA), the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR), or the Latin American Integration Association (ALADI). Or if there was an indirect influence coming from CARICOM or NAFTA. ”

The challenge of measuring integration, especially the role of specific regional organisations in the context of countries having overlapping memberships in various regional arrangements is also relevant in the Baltic Sea Region setting and spans across multiple domains well beyond trade. An example would be Latvia’s membership of the Baltic Council, Council of the Baltic Sea States, European Union and its affiliation to the Nordic cooperation. The most solid example of the Nordic footprint is the Nordic Council of Ministers’ Office in Latvia which “is a part of the Nordic Council of Ministers’ Secretariat and serves as a catalyst for the Nordic-Baltic cooperation in Latvia”. In one way or another, each of the mentioned formats and their support entities address the same thematic areas - higher education and research sectors being one such example.

Furthermore, the earlier outlined formats maintained in the Baltic Sea Region happen to share priorities and support the same initiatives by lending their strengths and targeted support to the overall success of certain promising multilateral collaborations. The Interreg Vb Baltic Sea Region Programme-funded project Baltic Science Network – a forum for higher education, science and research cooperation in the Baltic Sea Region – which is currently implemented in a form of an extension phase called “BSN_powerhouse” is the best example. As it has been elaborated earlier in the 2018 article “Research and Higher Education Cooperation in the Baltic Sea Region”, it is the most politically ornated multilateral initiative witnessed in the Baltic Sea Region. Initial guidance offered by RIKS might lead the platform’s user to additional similar examples of ‘entangled multilateralism’, meaning, a configuration of multi-level governance’s layers of multilateral cooperation frameworks which intersect via complementary support of a specific initiative.

Academic books and articles on regional consultations and collaboration, such as the ones mentioned in this blog entry, provide various typologies of regional organisations and arrangements, as well as present authoritative findings and detailed assessments about certain multilateral formats. RIKS, on the other hand, is a helpful compendium for an empirical dive into the complexities and shifting boundaries of the regional formats. RIKS is a promising gateway for every curiosity-driven user eager to embark on his or her quest for responses to the questions earlier raised by Richard Stubbs and Jennifer Mustapha about the nature and consequences of the ‘spaghetti/noodle/needle bowls’ characterising the contemporary landscape of regional multilateralism.