Of Trade, Regions and Power

Wednesday, 9 October 2019

If you want to gauge the state of health of regional governance, look at trade. Indeed, regional governance has traditionally been spurred by the strengthening of economic ties between different polities. Regionalism as a trade phenomenon preceded the emergence of a multilateral trade system: the first wave occurred with the 1870 Cobden-Chevalier Treaty between the United Kingdom and France, which laid the groundwork for a host of bilateral trade agreements in Europe. Indeed, the Treaty of Rome that founded the European Communities, and dates back to 1957, was first and foremost a trade agreement, followed in 1960 by the European Free Trade Association (EFTA).

Since the 1990s, following the Uruguay Round concluded in 1993, a new wave of regionalism took place. This prompted the proliferation of regional trade agreements (RTAs), especially Free Trade Agreements (FTAs), which have come to form a dense network of connections spanning four continents at the regional and sub-regional level. In these years, new trade agreements were concluded in regions such as Latin America (with the MERCOSUR), North America (NAFTA) and South-East Asia (ASEAN). By the early 2000s the inevitable spread of regional trade agreements seemed assured, to the point where it became “a fact of life”.

A Gloomy Picture

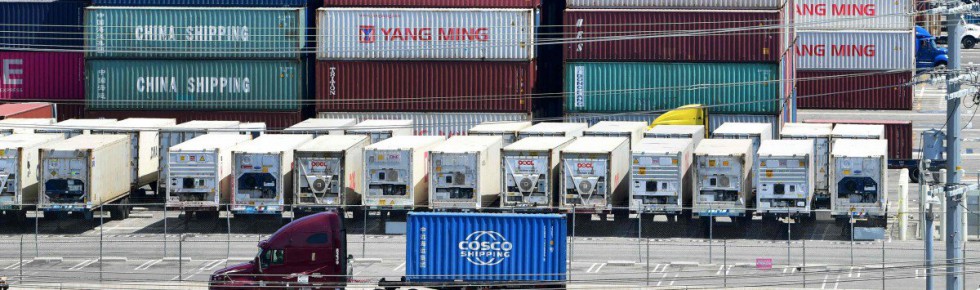

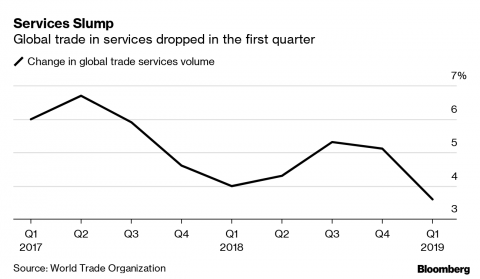

Today, however, the global trade and investment landscape is in a parlous condition. Many are the factors contributing to this dire conjuncture: the most evident is the US-China trade war that risks escalating into a geopolitical induced recession. In Europe, the tensions between the EU and Brazil over the large-scale fires in the Amazon could scuttle the long-awaited EU-MERCOSUR deal. In Asia, the growing Japan-South Korea rift has already spilt over into the trade domain, with Japan cutting its exports of chemicals that are indispensable for Koreas’ chip industry. Since his election, Donald Trump has loudly proclaimed his desire to renegotiate the North American Free Trade Agreement on the grounds that it has caused the damaging flight of American manufacturing jobs to Mexico. Before the election of President Trump, the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) between the EU and the US had already been frozen; although a new bilateral deal is being negotiated, it is unlikely to reach a successful conclusion, due to the reluctance of the EU to include agricultural products in the agreement and due to the hard-hitting tariffs that the American administration is levying against European firms. These factors are all symptoms of a regional order under strain and may precipitate the end of international trade as a driver for regional cooperation.

The current pushback against regional economic governance is thus problematic since it anticipates the return of a “shallow” multilateral order, in which countries engage in minimal economic cooperation and tighten protectionist policies to defend their purported national interests. This new trend of economic nationalism, threatens to dampen the efforts to find concerted solutions to common problems in favour of a political and economic approach that privileges quick fixes based on self-interest. According to the Peterson Institute for International Economics, the risks of trade protectionism indiscriminately affect both advanced economies and emergent markets. The most significant of these is that economic nationalism will prevent countries from being able to coordinate their efforts in the face of a global economic slowdown like the one that is apparently on the horizon. While historical analogies of the 1930s are often misused, it is useful to remind ourselves that during the Great Depression, back in 1929, many countries resorted to protectionist policies which only served to aggravate the crisis.

The EU as an infant leader

Considering all this, the EU’s trade agenda is set to face a rocky road. To rise to the challenge, the EU should stick to the goals already stated in the EU strategy Trade for All, which explicitly includes among its objectives the reinvigoration of the multilateral trade system. In particular, the EU should be instrumental in driving the process of reformation and modernization of the WTO; it will have to work diplomatically both with partners and rivals to ingrain the understanding that more reciprocity is needed for the global trade system to work and benefit all players. It should also insist on the proposition that a subset of WTO members alone can advance a given issue, with the possibility of other countries then joining later.

To continue to champion regional governance, the EU will have to resist the temptations of protectionism and economic isolationism .Rather, it should focus on the quality of its trade agreements, so as not to be outdone by rival regional projects, such as the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which has shown great potential in terms of trade and FDI improvement, but completely overlooks issues surrounding transparency, sustainability and the mitigation of corruption. The EU should also uphold trade regionalism for broader political reasons because regional trade clubs are more effective in dealing with global challenges such as environmental degradation and mass migration. In pushing this agenda, the EU can draw upon the hard evidence of the CETA agreement. Since its ratification last year machinery exports to Canada have risen by 8%, pharmaceuticals by 10%, exports of fruit, chocolate and wine respectively of 29%, 34% and 11%.

Ultimately, as it has been argued elsewhere, the biggest challenge for the EU will be psychological: for the first time, it will have to take the lead in shaping the global trade landscape: blustery waters await, and the EU will probably have to navigate them alone.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Filippo Blancato is a Research Intern at UNU-CRIS, and recipient of the UNU-CRIS Best Thesis Award at the College of Europe in 2019.

Contact: fblancato@cris.unu.edu