The Pacific Alliance’s Collective Identity and Insights on Its Sustainability

Angélica Guerra-Barón

PhD, Pontificial Universidad Catolica del Peru (PUC-Peru)

This blog is a part of the UNU-CRIS PhD Series featuring key findings from the dissertations of regionalism researchers across the world. The PhD Series aims to showcase new, original research in the areas of regional cooperation, regional integration, and regional governance.

21 January 2021 | #21.02 | The views expressed in this post are those of the author and may not reflect those of UNU-CRIS.

In 2010, the South American political context could have been interpreted as a clash of divergent approaches. Functional factors ‒ such as development models, political and ideological backgrounds, and economic approaches ‒ were predominantly determined by the decision makers’ bias. The predominance of this bias in decision-making processes affected any attempt to reach concrete and prompt results in political, as well as trade and investment aspects. Since then, this landscape has not changed significantly. However, since the late nineties, the intention of creating/strengthening identity elements for previous and forthcoming regional schemes has gradually come to the surface.

In 2012, it was within this complex milieu, the Pacific Alliance (PA) officially emerged. This group manifested the coexistence of the different identities held by Other intergovernmental and supranational groups. With each cluster wanting to impose its own narrative on the Alliance’s identity, these groups included the Bolivarian Alliance for the People of Our America (ALBA-TCP, in Spanish), the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (CELAC, in Spanish), the Andean Community (CAN, in Spanish), the Southern Common Market (MERCOSUR, in Spanish), the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR, in Spanish), and the Latin American Pacific Basin Forum (Foro ARCO, in Spanish).

Consequently, throughout the 21st century, South America developed a complex network of practices for different regional schemes. This is why the South American political landscape is now expressed through an identarian lens.

When analysing independent cases, it is rarely possible to isolate trends in the development of group identities. The literature on regionalism has crafted rich explanations to assess the impact of Hugo Chavez’ ideas and the geopolitical effects of those regional estimations. Complementarily, a large portion of the debate explaining new intergovernmental engagements has revolved around interests, institutional approaches, and economic models.

Keeping this in mind, it is worthwhile to ask: how have the agencies of South American States (Chile, Colombia, and Peru) built an alliance with their North American partner (Mexico)? How have they shaped different or differentiable narratives? Lastly, what role have non-state agents played ‒if any? These questions lead me to analyse the role played by languages, discourses, and narratives in crafting regional schemes.

By applying an ontological focus on the PA’s South American funding State Parties ‒ excluding Mexico ‒ from 2007 up to 2014, I deconstructed, identified and comprehended the formation of PA’s collective identity. For a broader audience, the answer might seem obvious: grouping is not a product, but a process. However, behind the apparent simplicity of considering the PA as a process, lie sophisticated explanations.

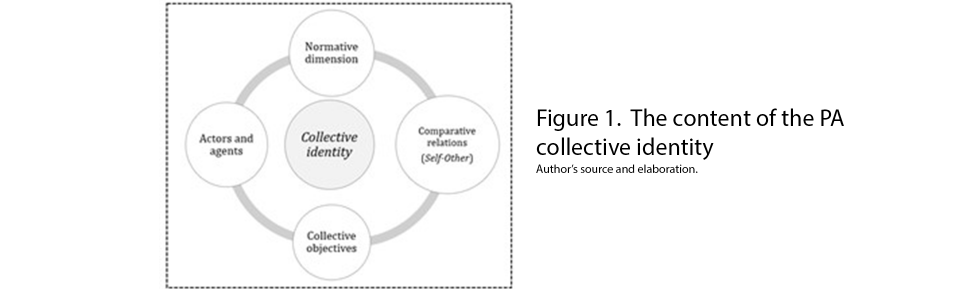

I departed from IR’s mainstream theories and constructivist works in favor of Social Identity Theory (SIT), by adopting Abdelal’s approach instead. Its theoretical richness in explaining the phenomenon of international relations allowed me to conclude that the PA’s collective identity consists of four intertwined variables: a normative dimension, the role played by norms in constructing the collective identity; the relational comparisons made by agents or actors between Self (State Parties) and Others (outsiders); the cognitive dimension of these players; and the collective objectives set by them (see Figure 1). The content of the PA’s collective identity cannot be fully tackled if impugned discourses are ignored.

This was an inductive qualitative study based on the interactive coding process of more than six hundred documents (written, oral, and visual). From these documents, five thousand textual quotes were discursively arranged in twenty networks. This methodological approach allowed me to uncover that the construction of the PA comprises different discursive stages from which it was possible to understand the group’s core narratives, as well as the interactions between actors and agents along the process. Still, its shifts and continuities do not respond to a logic of small or medium powers.

This variant of discourse analysis provided analytical tools to understand the role of language in the PA’s multidimensionality - within a political context. It also incorporated an inside-out approach to address the domestic, structural and regional drivers responsible for the PA’s inception and development, alongside its performance and sustainability.

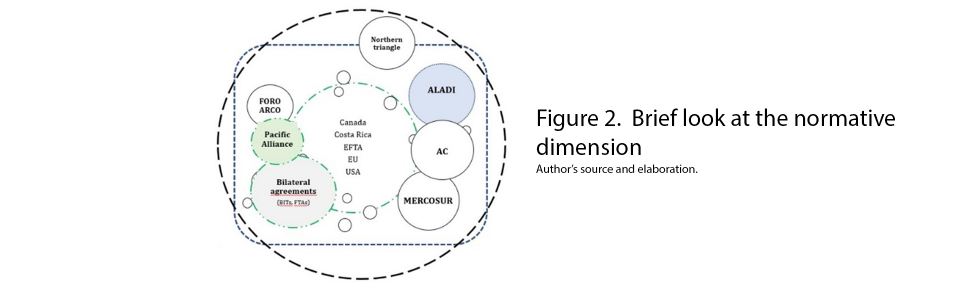

Of course, the narrative put forward by actors and agents involved in shaping an identity cannot be reduced to an economic model or normative aspects related to trade and investment (see Figure 2).

Evidently, the fact that the PA States share common practices partially explains the shifts that occurred throughout the creation of the group. These include adopting similar internationalization strategies with common trade partners (Canada, Costa Rica, EFTA, EU, and USA) and interacting as Associated States with MERCOSUR. Other developments include creating a framework of international investment agreements (FTAs and BITs), engaging in the Foro ARCO, and/or aligning their conduct with institutional arrangements administered by the Association of Latin American Integration (ALADI, in Spanish). These common practices have attracted observer countries whose entrepreneurial and political relations are intertwined.

Even though the evidence reaffirms the political and economic entanglement of the PA, it also proves the existence of narrative identity patterns. In a nutshell, the process wherein agencies interact with the structure to be recognized as a unit is what makes the State Parties a group. Through this process, the PA avoids the traditional conception of power characterized by a simplistic leader-follower hierarchy.

As you may have noticed, these findings are only evident when our attention goes beyond institutional arrangements. My research approach uncovers explanatory factors associated with the symbolic power of international recognition that is enacted through a relational network between the structure, agency, agents and actors involved. It thus, explains the factors lying beyond the idea of conforming to a group and its members.

The PA is more than “the new cool kid on the block” as Colombia’s former President, Juan Manuel Santos metaphorically said. The process of its construction explains how a domestic and subregional order can be kept separate from the notion of development envisioned by each of its creators. Following this logic, the creation process of the PA continues no matter the cosmovision and ideological preferences of individual presidents.

In my PhD thesis, I was able to produce applied knowledge based on relevant evidence that helps understand the significance of PA’s emergence. Additionally, it explains and provides clues to understand how ‒ and, to a lesser extent, why ‒ domestic and regional decisions were taken, creating insights into the theoretical richness of SIT that nurtures IR studies; thus, aiding the comprehension of dynamic and unfinished collective identities.