Of Blind People, Elephants and the Pacific Alliance Integration: Institutionalist Account and Proposals for Change

VII Summit of the Pacific Alliance, Santiago de Cali (May 2013). Image credit: Gobierno de Chile, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Ana Maria Palacio Valencia

Visiting Research Fellow, UNU-CRIS

This blog is a part of the UNU-CRIS PhD Series featuring key findings from the dissertations of regionalism researchers across the world. The PhD Series aims to showcase new, original research in the areas of regional cooperation, regional integration, and regional governance.

13 July 2021 | #21.15 | The views expressed in this post are those of the author and may not reflect those of UNU-CRIS.

The Pacific Alliance (PA), established in 2011, presents itself as a sui generis ‘mechanism for regional integration’ comprising Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Peru. This sui generis character is contestable on many grounds, including institutional, political and ideational. This contribution examines the PA from an institutional perspective unpacking its design, ideational underpinnings and questioning whether its current institutional framework is sustainable to support the association in the long term.

The institutional framework of the PA evidences an unresolved tension. The PA must ensure an adequate institutional framework pushing towards institutional enlargement, centralisation and delegation of tasks to deal with regular interstate cooperation and collective action by the PA member states. In contrast, the constraints towards institutional adjustments emerging from the underpinning ideas and negative perceptions about the performance of pre-existing regional institutions in Latin America (LA) create resistance to ‘upgrade’ or enlarge the current organisational structures and legal regime.

Characterising the PA’s Institutional Framework

The PA represents an informal intergovernmental institution (IIG) that is not an international organisation invested with international and domestic legal personality. The PA has consensual decision-making, and a decentralised organisational and task-related structure. This institution follows an informal approach to institution-building.

Organisational structures encompass a spectrum of formal and informal arrangements. These structures have, in many instances, responded to demand-based or problem-based approaches in their establishment. Growth and specialisation of organisational structures occur through informal means, which evidences the effects of the ideas of flexibility and pragmatism that frame the PA. The PA’s institutional framework shows a hierarchical, top-down structure that is non-permanent and non-dedicated.

PA’s intergovernmental design also relies on presidential leadership; it is flexible enough to accommodate trans-governmental collaboration networks in several fields, including intellectual property and innovation. The PA’s institutional framework presents a low degree of legalisation through arrangements (guidelines, memoranda, guiding principles, and declarations) that intentionally use imprecise language and non-binding rules. The scope of the PA is dynamically growing to cover not only trade and investment issues but also productive transformation, financial integration, innovation, GVCs, and other non-economic topics.

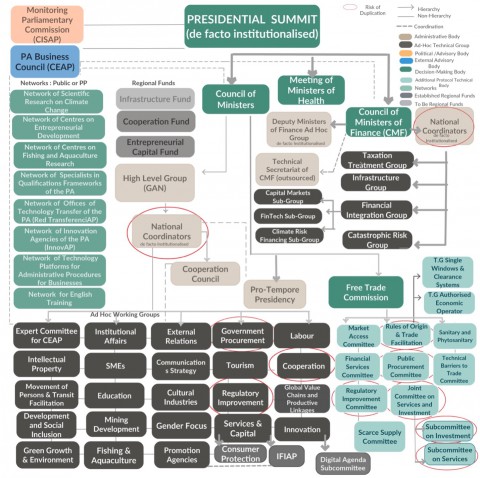

Although structures have developed more informally in the PA than in other regional organisations across LA, they are still present and continue to build incrementally and in layers. The following figure presents PA’s organisational structure unveiling a web of formal and informal institutional arrangements more complex than governments in the PA acknowledge and portray.

Author’s analysis based on treaty documents, presidential declarations, secondary sources and interview data

Image credit: Author

Institutional Underpinnings

The PA’s institutional design results from underlying cooperation problems, including uncertainty and commitment problems. Ideational underpinnings, such as open regionalism, deep integration, flexibility, and pragmatism also contribute to explain its design. External institutional environments have also played a role in its institutional design outcomes.

Cooperation problems and characteristics of the PA members in the aggregate, such as regime-type similarities and preference homogeneity, rationally explain at the micro-level the PA members’ choice for specific treaty rules in PA’s international agreements.

The ideas of open regionalism and deep integration worked as cognitive programs determining the initial focus on trade and investment. They were roadmaps defining the scope and issue areas to address regionally. Open regionalism and deep integration were vital for defining PA’s (formal) economic objectives, instruments, and agenda. The frames of flexibility and pragmatism played a double legitimising role, according to the empirical evidence. These normative foreground ideas legitimise not only the programs of open regional and deep integration but also PA’s institutional architecture as a whole.

Normative Proposals

The realisation of the PA’s (formal) goals demands policy coordination and harmonisation, and the development of other regional public goods. The current organisational structures and the limited scope of its economic rules are insufficient to cope with these demands and processes of deepening, membership enlargement, and agenda expansion. The high informality of PA’s institutional framework cannot secure long-term accountability for the PA’s work or the transparency it pursues.

Demands to further economic regionalism towards the free movement of goods, services, capital, and people in the PA will require adjustments to the institutional framework. Shortcomings of intergovernmental approaches to rule-setting could be addressed through periodic rounds of treaty negotiations that help to build political support for package deals. Principles-Based regulatory harmonisation could also assist in managing the shortcomings of its current regulatory regime.

Institutional entrepreneurs should mobilise incremental adjustments, including integrating a centralised administrative body with medium-term agenda-setting, coordination and monitoring roles. The PA requires a permanent Secretariat with administrative and technical tasks and a policy-shaping capacity. Revisiting the composition of the Council of Ministers to allow for flexible configuration will help the PA make decisions with greater policy impact than the current results.

In brief, although the PA exhibits marginal new traits when compared to other regional institutions, it is neither a sui generis model for economic regionalism nor shows an innovative institutional design. Although these two frames generate momentum for the PA, they find no basis in the PA’s institutional framework. Intergovernmentalism, consensual decision-making, organisational and task-related decentralisation are, on the contrary, common characteristics within regional institutions around the globe.

Considering the weight that presidential leadership has for the progress of the PA goals, its soft approach to rule-making, and regular resort to informal and direct negotiations to solve differences, the PA has strong political grounds.

Discussing the issues above is timely, considering the large amounts of resources and time that states invest in these regional projects and the sunk costs of undertaking them. On its 10th anniversary of foundation, the PA prompts several concerns concerning its effectiveness and ability to deliver on the expectations raised in the last years, let alone its expanding goals.

For a deeper analysis, please visit the thesis monograph. Further commentaries and information about the progress of the PA’s integration project are also available at Shaping the Pacific Alliance.