Region-building in the Caspian Sea Basin: Do Recent Developments Point Towards an Integrated Region?

Natalia Skripnikova

Former Research Intern, UNU-CRIS

Servaas Taghon

Former Research Intern, UNU-CRIS

10 March 2022 | #22.05 | The views expressed in this post are those of the author and may not reflect those of UNU-CRIS.

This post draws on the recently published policy brief The European Union’s Approach to the Caspian Sea Region: The Energy-Environment Nexus by Natalia Skripnikova and Servaas Taghon.

Please note: This blog was accepted for publication on 31 January 2022.

Regions take many shapes and forms and are often interpreted differently depending on the actors defining them. Previously, when people brought up regions, they referred to a space occupied between the local and the national levels within the state. Still, next to these ‘sub-national regions’ and ‘micro-regions’ there are also the so-called macro-regions placed between the national and global levels. Whenever attempts to define the constituents of a region are made, we intuitively tend to refer to the ‘piece’ of territory it holds. Following this line of reasoning, regions are static expressions of geographically fixed units. Yet, what eventually constitutes the make-up of regions is a rather complex image painted by politics, culture, identity and economy. Subsequently, regions are constantly under the process of being shaped, altered or even dissolved. Specifically, the processes of this regional ‘shaping’, occur both internally and externally through constitutive stages like territorial shaping, symbolic shaping, institutional shaping and the presence of an ‘identity’.

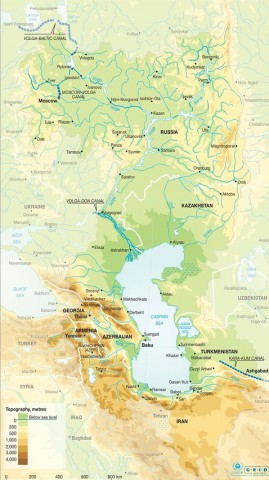

The Caspian Sea Basin provides an interesting case of region building processes especially in the light of recent developments including the building of energy corridors, emerging environmental pressures and resolving of the legal status of the Caspian Sea in 2018. This state of play provokes the following question: can we speak of an integrated Caspian Sea region? Geographically, the Caspian Sea coastline is shared among five littoral states: Russia, Iran, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan. Historically, Iran and Russia historically have had full state control over the sea. However, after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, three new states were formed with access to the Caspian Sea: Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. Since the Caspian Sea is a landlocked body of water, these three countries remain landlocked, while Iran and Russia have open sea access. Today it is challenging to talk about a singular Caspian identity, as the commonality among the countries is far more fragmented. According to Anker et al. (2010) Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan are the countries that fit best into the concept of a Caspian region, since they share features like being post-soviet, having Russian as the first or second language, small populations, not clearly belonging to other regions, Caspian littoral, land-locked, oil and gas export and transit, Muslim and Turkic.

Cartographer: Ieva Rucevska and Philippe Rekacewicz, GRID-Arendal. View the HD version of the map here.

The Caspian Sea region is rich in natural resources both non-renewable (e.g. fossil fuels, metals, uranium) as well as renewable – hydropower, sunlight and arable land. For several decades, the legal status of the Caspian Sea had been disputed. Only in 2018, the littoral states have signed the Convention on the Legal Status of the Caspian Sea. “The Convention stipulated that each state shall have its national sector of the seabed, while the surface of the sea should be treated as international waters.” The evolutional processes within the region, support the theoretical propositions of the Caspian Sea’s internal. Reaching the agreement has become a new milestone for the Caspian Sea region and has opened new opportunities to foster closer relations between the littoral states and outside world.

External actors also contribute to similar tendencies of shaping the Caspian Sea region. The two most prominent examples could be the European Union (EU) and United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). The EU’s relations with the Caspian countries are foremost motivated by energy interests, despite the EU not having a coherent approach towards the region. Today the EU applies a fragmented approach, which means that some countries have concluded partnerships whether as part of the European Neighborhood Policy (ENP) and Eastern Partnership (EaP) or maintain strictly bilateral relations, and others only collaborate with the EU on a small scale. In many ways, it seems like Brussels’ approach reiterates the incoherence and lack of institutionalisation around the Caspian Sea. However, when it comes to creating an environmental regime, the EU has been organising and supporting initiatives that regard the Caspian as a region. Subsequently, macro-regional environmental cooperation could be one of the constitutive factors in shaping the Caspian.

The emerging Caspian environmental regime was broadly supported by international actors. In 1998 the Caspian Environment Programme (CEP) was launched as an umbrella platform to develop environmental cooperation between the littoral states. The CEP operation was supported by the EU, United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), UNEP and the World Bank. In 2003, all five Caspian littoral states signed the Framework Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the Caspian Sea, also known as the ‘Tehran Convention’. It laid down the general requirements and the institutional mechanism for environmental protection in the Caspian region. The Tehran Convention also stipulated the establishment of a Secretariat. The Tehran Convention Interim Secretariat (TCIS) is hosted and administrated by UNEP’s Regional Office for Europe in Geneva, Switzerland. This makes the UNEP one of the most important international actors in facilitating the environmental cooperation in the Caspian Sea region.

Given the recent developments, can we assert that the Caspian Sea Basin can be classified as a region? Theory on region building and regionalism shows that such claims should be approached with great caution. While certain macro-regional elements are indeed present, at the same time Caspian countries remain very differentiated. The absence of one overarching ‘Caspian identity’ in particular seems to question the existence of a Caspian region. However, a couple of events in the last two decades have given scholars food for thought to view the Caspian as an emerging region. Internally, the Convention on the Legal Status of the Caspian Sea can be considered as a breakthrough in establishing the littoral states as legally equal, contributing to building their Caspian commonalities. Externally, several international actors approach the Caspian Sea as a region when it comes to environmental policies and initiatives. By creating regional environmental institutions, the Caspian is being constructed as macro-region rather than an arbitrary collection of states.