A Manifesto for Regionalism in Africa

Associate Research Fellow at UNU-CRIS, Professor in the School of Global Studies (SGS) at the University of Gothenburg

Chair for Multi-Level Governance, Albert-Ludwigs Universität Freiburg

31 January 2023 | #23.02 | The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and may not reflect those of UNU-CRIS.

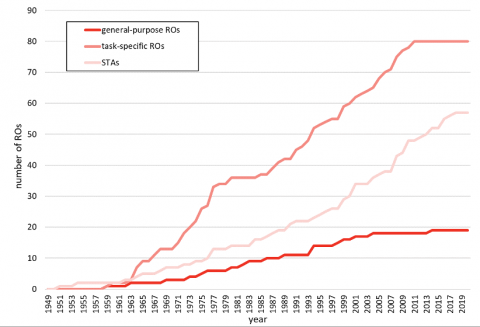

There has been a steady increase in regional organisations (ROs) in Africa since the end of colonialism. A range of these were created in the early period after independence in the 1960s and 1970s. Whereas some of these ROs have since been dissolved, many are still in existence, albeit with a different name, membership or mandate. While rather few ROs were established in the 1980s, the number more than doubled between 1990 and 2020, resulting in an aggregated total of 156 ROs currently in existence, which are divided into three main types.

First, the African Union (AU) and the Regional Economic Communities (RECs), such as the East African Community and the Southern African Development Community (SADC) are the most well-known cases of general- and multi-purpose ROs. Second, there are a large number of task-specific and specialized ROs, such as the Inter-African Coffee Organization. Third, the AU and the RECs also includes a number of specialised and technical agencies (STAs), which basically operate in a similar fashion to the more autonomous task-specific ROs. Figure 1 shows the development of the three categories over time.

Figure 1: Number of ROs Over Time by Type of Organisation

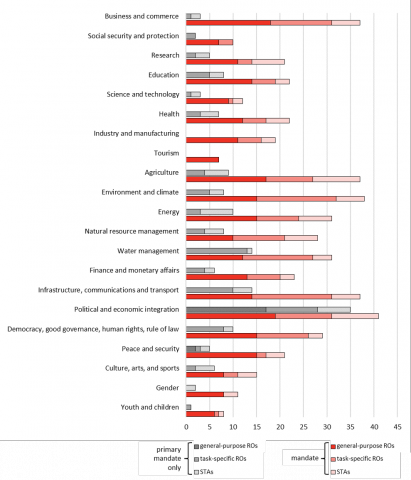

The 156 ROs in Africa are unevenly spread over different policy fields. As depicted in figure 2, a few policy fields include only a small number of ROs (such as gender and youth and children), whereas several other policy fields involve more than 30 ROs (such as political and economic integration, agriculture, business and commerce). In between these poles, there is a large group, which include between 10 and 30 ROs (such as health, research, etc.).

Figure 2: Number of regional organisations across policy fields

Note: The number presents information of the primary policy mandate of ROs (grey bar) and the aggregated mandate of ROs (green bar). For a full list of ROs in all policy fields, see Söderbaum and Stapel 2022a.

Drawing on decades of our own research in this area (and some more recent papers), we outline a manifesto for how these ROs can meet the continent’s security and development needs.

Article 1: Get realistic

A significant number of ROs have over-ambitious goals and policy mandates, which often results in a lack of focus and prioritisation between different goals and activities. The mismatch between ends and means is widespread across sectors and types of ROs and has been increasing due to over-expanded portfolios of primary and secondary mandates. In order to optimise performance, open-ended wish lists need to be turned into realistic work programmes with clear priorities.

Article 2: Strengthen capacities

Too often there is a misfit between ambitions and organisational capacities. Weak organisations are unable to mediate and coordinate diverging national interests and foster cooperation for the common good, which often results in discord or that one or several member states “hijack” the organisation for self-serving interests. Strengthened organisations require material resources but institutional reform must go beyond the issue of funding itself and needs to focus on all the necessary institutional, epistemic and political capacities that make ROs perform better. There is also a need for developing better performance-based monitoring and evaluation frameworks. Finally, making ROs fit for purpose cannot be separated from domestic institutional capacities.

Article 3: Ensure national buy-in and political leadership

Many ROs remain detached from national development strategies and the development needs of their member states, which make them both unsustainable and less relevant for tackling Africa’s development challenges. Oftentimes ROs lack the necessary political support from their member governments. A reciprocal process is therefore required whereby RO secretariats build stronger links to member states while member states simultaneously invest political capital (and financial resources) to make ROs work.

Article 4: Dismantle dysfunctional organisations

Several ROs in Africa are dysfunctional and fail to deliver. Radical reform or dismantlement happens only rarely, which has resulted in the growth of an increasing number of underperforming ROs; or what has been referred to as “zombie” organisations. Although the number of new ROs have been reduced during the last decade, many general-purpose ROs have created a steady stream of new STAs, some of which are weak or ineffective. There is a need for a new paradigm in Africa whereby dysfunctional ROs are identified and either reformed or even dismantled.

Article 5: Create new organisations

Despite an excessive number of organisations and an inflation of policy scopes in Africa, a few policy fields still lack collaborative frameworks and functioning ROs and STAs. New, integrated ROs and STAs may also be motivated in the case of detrimental overlap between competing ROs. There needs to be a diagnosis of what would be the added value and contribution of new ROs and STAs compared to alternative strategies. Merely creating new organisations will add little value unless member states are willing to cooperate and invest in new organisations.

Article 6: Diagnose and manage inter-organisational overlaps

Overlaps between ROs have become a defining feature of the institutional landscape of many policy fields. These overlaps occur through a complex web of multiple and crisscrossing ROs, policy scope expansion, the accession of member states and the creation of new ROs. Although overlaps are not always harmful, they often result in inter-organizational competition, fragmentation, and underperforming ROs. Relevant actors need to improve their capacities to diagnose as well as manage inter-organisational overlaps, but also to prevent member states to use overlaps strategically.

Article 7: Open up to non-state actors

Many ROs in Africa remain rather “closed” entities with limited access for non-state actors (NGOs, business, citizens, academia, etc.). When non-state actors are invited, they are often either co-opted or involved merely as experts, consultants or service providers at lower levels. Involving non-state actors brings a range of benefits: (i) they can anchor ROs in the actual needs of their citizens, (ii) they contribute unique input and competencies at various stages of the policy cycle, and (iii) they keep member states in check through monitoring and increased transparency, accountability and legitimacy, which will increase the performance of ROs. Notwithstanding, opening up to non-state actors needs to be done in a strategic fashion, where and when it is most productive.

Article 8: Take charge of donor funding

Many ROs are extremely dependent on donors and foreign funding, which sometimes impacts negatively on their performance and disturbs the incentive structures for African actors. However, without external funding, many ROs would have to drastically reduce their work programmes and some organisations would have to be dismantled. There is a need for a radical rethinking of the relationships with donors where African member states take charge of donor relationships in a manner that contributes to RO performance and Africa’s development challenges. For instance, earmarked project funding, donor-driven programmes and trust funds that circumvent and bypass ROs should be reduced in favour of more autonomy and discretion for African-driven programmes.

For some of our recent policy-oriented studies, see:

Fredrik Söderbaum and Sören Stapel (2022a) “Agenda 2063 and the role of Africa’s overlapping regional organisations”, Discussion Paper No. 137, Maastricht: ECDPM.

Fredrik Söderbaum and Sören Stapel (2022b) “Regional organisations and Africa’s Development Challenges”, UNU-CRIS Policy Brief 06:2022, Bruges: UNU-CRIS.