Confrontational and Cooperative Regional Orders: Managing Regional Security in World Politics

A UN Security Council Meeting on Denuclearization in progress at the United Nations in New York City, 2017. Image credit: U.S. Department of State from United States, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Ariel Gonzalez Levaggi

Associate Professor, Pontifical Catholic University of Argentina

This blog is a part of the UNU-CRIS PhD Series featuring key findings from the dissertations of regionalism researchers across the world. The PhD Series aims to showcase new, original research in the areas of regional cooperation, regional integration, and regional governance.

30 June 2021 | #21.14 | The views expressed in this post are those of the author and may not reflect those of UNU-CRIS.

This post draws on the recently published book Confrontational and Cooperative Regional Orders: Managing Regional Security in World Politics, based on a dissertation submitted by the author to Koç University, Turkey.

Regional orders have become a central feature of world politics. Regions change as global and domestic dynamics unfold. Gonzalez Levaggi argues that the complex interaction between democratisation and liberal political coalitions, in addition to non-existent external intervention builds a cooperative security system. On the contrary, increasing authoritarian domestic and nationalistic political coalitions among key regional players, in addition to external intervention, builds a confrontational security system.

During the San Francisco United Nations Conference on International Organization (UNCIO), participants did not reach a proper definition of region, but did provide a guide to identify regions in world politics based on geographical proximity, community of interests and common affinities. Since the Cold War, regional dynamics in a global world have been at the center of international security concerns. They draw public attention from the Israeli challenge to the Iran’s Nuclear Plan to the consequences of the Union of South American Nations’ demise. Some regions like South America have developed a (fragile) peaceful framework in which interactions are characterised by a non-coercive agenda, while others never reached that threshold, thus regional tensions and conflicts such as the Caucasus, remain.

The Puzzle

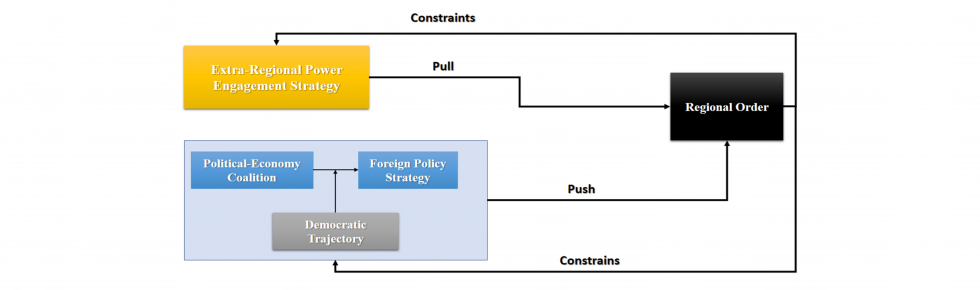

When analysing regional dynamics, most of the approaches towards regional transformation are grounded in some interaction between the second and third image of analysis that explains the ‘second-and-a-half’, sub-systemic, or regional level phenomena. In the case of realist and liberal approaches, the type of international order is fundamental to define not only how states react to a different environment, but also how great powers intervene extra-regionally. At the same time, domestic factors constrain foreign policy strategies, thus influencing regional options. In this sense, the central theoretical puzzles are: How do extra-regional great powers influence regional orders? How do domestic factors shape regional transformation?

Image credit: Author

The Argument

The strategic interaction of regional powers within a particular region usually impacts on the regional orders, sending them in a more cooperative or conflictive direction. However, the sources of that interaction mainly lie in the type of governing political-economy coalition (nationalist/internationalist), while the institutional trajectory (towards democratisation or not) is also important as an intervening variable that could push states into a more assertive or cooperative stance. A cooperative trajectory does not necessarily lead to long-term institutionalisation and successful regional conflict management but provides additional incentives to converge regional interests. On the other hand, a more conflictive environment would definitively harm regional norms and institutions, with the additional risk of increasing political, and even military, tension.

The book offers a push-and-pull-framework to explain the evolution of cooperative and conflictive regional orders. As the major finding, it shows that soft engagement strategies from great extra-regional powers and internationalist domestic coalitions framed in a stable democratic polity are forces of peaceful interaction, while hard engagement strategies from great external powers plus nationalist coalitions within democratic backsliding in key regional powers present negative outlooks for regional cooperation.

The Central Eurasian/Black Sea region and South American are examples of conflictive and cooperative regional orders in which the push-and-pull framework works differently. In the case of Central Eurasia, the regional order moved from balance of power to a limited regional concert, and back again to a power-to-power setting. A hard engagement from the United States (US) – due to military intervention, economic sanctions, and balancing practices – and the conjunction of nationalist political coalitions and democratic backsliding in Turkey and Russia affected the regional trajectory negatively. For South America, the transformation from rivalry to a security community was consolidated in the 1990s after a major change in the 1980s. Despite changes in the domestic scene from internationalist to nationalist coalitions and vice versa, the US regional retreat and the rise of China, the relations between Argentina and Brazil and the regional cooperative environment remained peaceful, although loosely institutionalised.

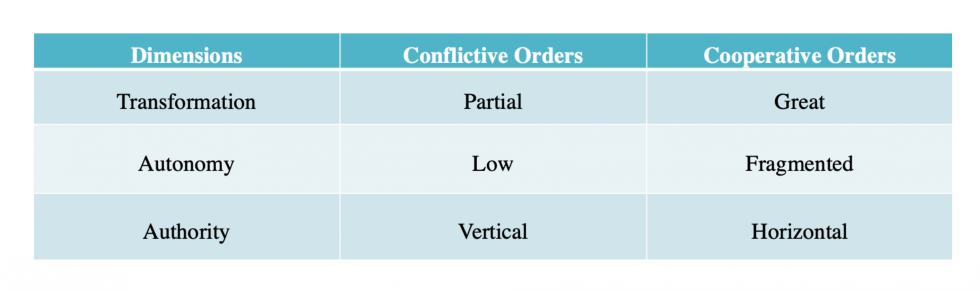

Image credit: Author

The study of the transformation, autonomy, and authority of governing arrangements among key regional actors that manage security and institutional cooperation differently presents a novel approach to compare non-Western regional orders, helps to forge a better integration between IR disciplinary approaches and area studies, while filling a literature gap on the interactive sources of regional change.