Post-conflict Self-determination Referendums: Serving Peace and Democracy?

Image credit: Ranjit Bhaskar of Al Jazeera English, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Kentaro Fujikawa

Fellow, International Relations, London School of Economics (LSE)

This blog is a part of the UNU-CRIS PhD Series featuring key findings from the dissertations of regionalism researchers across the world. The PhD Series aims to showcase new, original research in the areas of regional cooperation, regional integration, and regional governance.

22 June 2021 | #21.10 | The views expressed in this post are those of the author and may not reflect those of UNU-CRIS.

Post-conflict Self-determination Referendums: Useful or Dangerous?

Self-determination conflicts are notoriously difficult to resolve. To settle protracted conflicts such as in Eritrea, East Timor, Southern Sudan, Bougainville, or Northern Ireland, post-conflict self-determination referendums have been held (or promised) based on the consent of the central governments concerned. Indeed, policymakers seem to think that these referendums contribute to the prospect of peace and democracy in war-torn societies.

However, some scholars have criticised the use of referendums for self-determination. According to them, referendums have a ‘winner-takes-all’ zero-sum nature. When used for the fundamental question of self-determination, referendums worsen tensions, which could lead to violence. Massive violence after the 1999 referendum in East Timor is a case in point. In fact, to democratically ascertain the wish of the population, an oft-forgotten alternative exists—an indirect vote where an elected legislature decides on the question of self-determination.

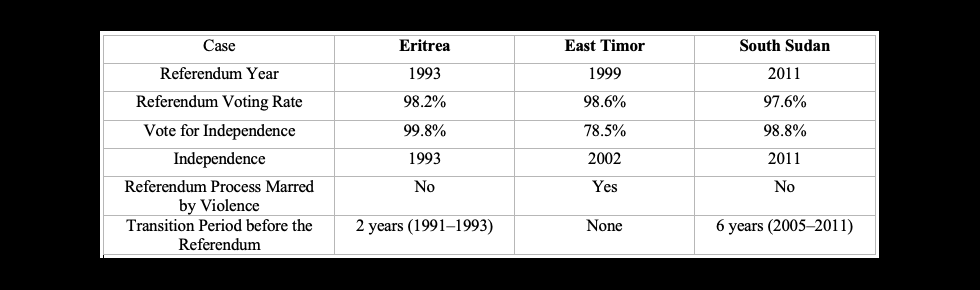

Facing the two divergent understandings of the utility of referendums in conflict resolution, I analysed three cases of post-conflict self-determination referendums—Eritrea in 1993, East Timor in 1999, and South Sudan in 2011—and investigated their rationale and impact on peace and democracy.

In the three cases, I observed similarities despite their contextual and historical differences. Overall, self-determination referendums have value in settling the original conflicts (e.g., Sudan–Southern Sudan), but they have mixed (including unintended, negative) impact on peacebuilding within newly independent states (e.g., South Sudan).

Analyses: Eritrea, East Timor, and South Sudan

In my doctoral thesis titled, Serving Peace and Democracy? The Rationales and Impact of Post-conflict Self-determination Referendums in Eritrea, East Timor, and South Sudan, I focused on three areas: (1) rationales behind referendums (instead of an indirect vote); (2) the referendums’ impact on resolving the original self-determination conflicts; and (3) their impact on post-conflict peacebuilding inside the newly independent states: accommodation of internal tensions, democratisation, and international attitudes.

Referendum Information in the Three Cases. Image credit: Author

On rationales behind a referendum, once self-determination was agreed upon, pro-independence movements, supported by international actors, strongly demanded a referendum. There was a worry that an indirect vote would increase the likelihood of a rigged outcome; for example, representatives might be bribed or threatened in an indirect vote.

The referendums had some utility in resolving the original self-determination conflicts. While the commitment of the powerful international and domestic actors to the peace processes was crucial to resolving these conflicts, holding a referendum was useful to secure international commitment. In East Timor and Southern Sudan, intensive international pressure ensured that the Indonesian and Sudanese governments accepted the referendum results.

Furthermore, the referendums—the least controversial method of self-determination which ascertains the wish of the population quantitatively and directly—were necessary for central governments to justify their territories’ detachment to domestic actors against independence. In Eritrea, Ethiopians were angry that only Eritreans were allowed to vote. In East Timor, hardline Indonesians claimed that the United Nations manipulated the referendum. But, in both cases, their resentment would have been more intense if a referendum had not been held or if self-determination had been exercised through an indirect vote. Meanwhile, I did not find that the zero-sum nature of referendums was relevant even in East Timor.

When we turn our eyes to peacebuilding within new states, the referendums’ impact is far more ambiguous. There is no evidence to suggest that the referendums helped accommodate tensions within the newly independent states. Pro-independence leaders were united over the cause of independence during the referendum process, but their rivalry—Xanana Gusmão vs Mari Alkatiri (East Timor), and Salva Kiir vs Riek Machar (South Sudan)—re-emerged once independence was secured.

A total of 3.9 million people registered for the self-determination vote in South Sudan, 2011. Image credit: Al Jazeera English, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Regarding the referendums’ impact on democratisation, in Eritrea and South Sudan, the transition period leading up to the referendum (two and six years respectively) was used by the dominant political groups to consolidate their exclusive power over the territory concerned. After the referendum, neither entity democratised, though this failure to democratise cannot be directly attributed to the referendum. In contrast, East Timor, which had no transition period before the referendum but benefited from the UN transition period after it, has become the most democratic country in Southeast Asia. It has been recognised that the experience of casting a vote on the fundamental question of self-determination has led to a higher voter turnout at subsequent elections and more generally contributed to a participatory democracy in East Timor.

Finally, across all three cases, the referendum experience led to excessive optimism among international actors. They wrongly assumed that the unity of pro-independence leaders and citizens would continue after independence, that this unity indicated no tensions existed within the pro-independence movements, and that it meant democratisation would not be difficult. Failure to understand the local dynamics had real consequences. In East Timor, the UN peacekeeping forces withdrew hastily based on this misplaced optimism, making it impossible for the UN mission to effectively deal with the 2006 crisis. In South Sudan, the international actors focused more on development than politics after independence, limiting their ability to prevent the 2013 civil war.

Conclusion and Future Research

The post-conflict self-determination referendums have mixed impact on war-torn societies. However, some of the negative impacts could be easily mitigated. Notably, the excessive optimism by international actors is a matter of perception and thus, not inevitable.

In the future, research should be extended to other post-conflict referendums. One example would be Bougainville’s post-conflict self-determination referendum in 2019. This referendum was characterised by a long transition period (18 years) and its non-binding nature. Studying how these characteristics have affected peace processes will help us further our understanding of post-conflict referendums. Similarly, whether other post-conflict referendums such as the Northern Ireland referendum in 1998 and the Columbian referendum in 2016 (both deciding on a peace agreement) had any lasting impact on the war-torn societies is worth studying.