Towards a Comeback of Regionalism? Prospects for Latin American Integration During the New Tide of Leftist Governments

Research Intern, UNU-CRIS

12 May 2023 | #23.05 | The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and may not reflect those of UNU-CRIS.

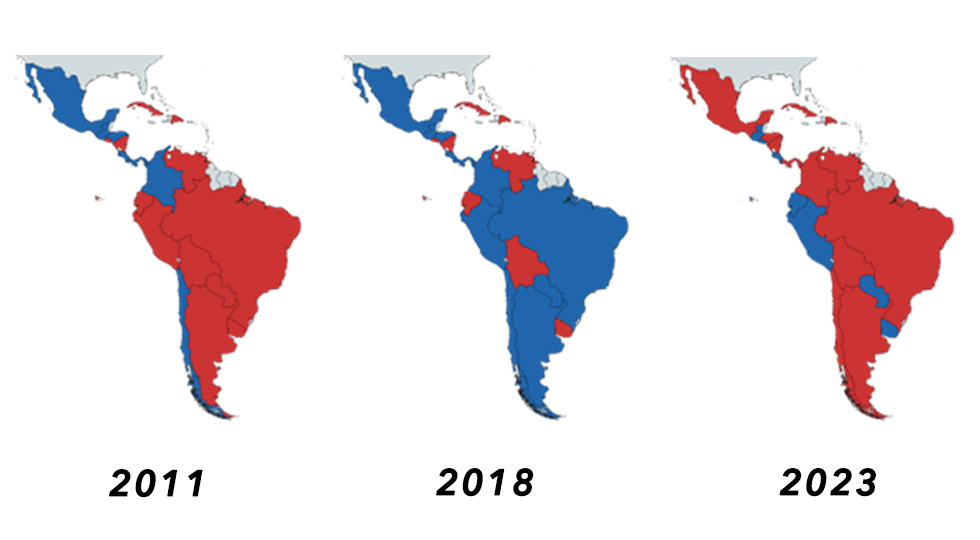

In April 2023, the Brazilian and Argentine governments raised hopes of a revitalisation of Latin American regionalism. They both announced their return to the Union of South American Nations (UNASUL) as full members. UNASUL is a regional organisation that was created in 2008 and became emblematic of the Pink Tide (in Portuguese Onda Rosa and in Spanish Marea Rosa) era in Latin America. The term refers to the elections of leftist or centre-left political leaders in the vast majority of the region during the first decade of the 2000s, leading to an ideological convergence in the region. During this tide, Latin American governments were successful in institutionalising regional cooperation with a stronger political and social dimension. However, UNASUL went into hibernation in the 2010s. At that moment, many Pink Tide governments were faced with the consequences of economic stagnation and public corruption scandals, leading to electoral setbacks. In the aftermath, a number of far-right politicians and parties emerged, the most emblematic being Jair Bolsonaro, a polarizing figure elected president of Brazil in 2018. This period, covering most of the 2010s is designated as Blue Wave (Onda Azul or Marea Azul). Contrary to their predecessors, leaders from the right political spectrum had a less integrative vision of Latin American regionalism and rejected a progressive regional agenda regarding human rights, environmental protection and economic policies.

Pink Tide (2011), Blue Tide (2018), Pink Tide 2.0 (2023) at their respective peak

Photo: Foro de São Paulo, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Recent elections of left leaders in Latin America, such as Gustavo Petro in Colombia, Gabriel Boric in Chile, and the re-election of Lula in Brazil, have spurred discussions of a possible revival of politically driven regional integration projects. However, the relationship between Latin American regionalism and political ideology is complex. Pink Tide 2.0 must tackle new political challenges and visions for regional governance differ substantially, thus limiting the opportunity for greater regional integration in the region. The left might be back in Latin America, but regionalism might not follow suit this time.

Latin America’s challenge to speak with one voice

Current regional and domestic contexts in Latin America differ from twenty years ago and are arguably less favourable to a successful Pink Tide 2.0. The COVID-19 crisis hit the Latin American region particularly hard, partly due to the lack of regional coordination among countries. The already existing structural inequalities in Latin America and the Caribbean along with poor regional coordination made the region’s healthcare systems even more vulnerable and the economic recovery more difficult. While blocs like the African Union, the European Union, and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations coordinated on response protocols and negotiated vaccines for their member countries, Latin America experienced a hollowing out of regional political capacity and a tendency towards national ad hoc measures.

Moreover, although some governments have shown commitment to regional cooperation, for instance, Chile, Brazil and Colombia, other countries have a more nationalist and anti-globalist stance. Mexico’s president Andrés Manuel López Obrador has been pushing for a self-sufficient energy policy for Mexico and stronger economic sovereignty. The same case can be observed with Maduro in Venezuela or Ortega in Nicaragua, indicating that there is no leftist template for Latin American regional integration. For example, after criticism by the Argentine government concerning human rights abuses in Nicaragua, Daniel Ortega refused to support Argentina’s bid for the two-year presidency of the regional forum CELAC. Neither Maduro nor Ortega attended the latest CELAC meeting in Buenos Aires. There are also rising tensions between Peru, Argentina, Bolivia, Colombia, and Mexico due to the recent impeachment of Peruvian President Pedro Castillo in December 2022. Political divisions within the Pink Tide 2.0 limit the prospects to deepen regional integration.

Domestic and global obstacles to Latin American Integration

In many Latin American countries, the far-right, even if in opposition, is much stronger now than it was before. Throughout the region, societies have become more polarised, experiencing a rise in political violence and an overall feeling of anti-incumbency, which puts the Pink Tide 2.0 leaders under pressure. Despite having won elections, the legitimacy of their mandates has been questioned by politicians seeking to expand their influence over right-wing politics at the national level. Consequently, a main priority for Pink Tide 2.0 leaders is to gain control over national narratives regarding economic and employment crisis, social inequalities and poverty reduction. Whereas the governments of first Pink Tide, such as Evo Morales and Hugo Chavez, were more concerned with political ideology, today’s Latin American leaders are more keen to appear as national consensus-builders. In this sense, their agendas are also inward-looking and formulate fewer ambitions for greater regional integration.

Presidential Summit of Latin America and the Caribbean, January 2023

Photo: European Union

Finally, the international context is also different from the first Pink Tide. While the importance of the European Union and its model for regional integration has declined in Latin America, China has become a key partner. Beijing’s protagonism in the region has led to a growing economic dependency by Latin American countries, and, as a consequence, to a decline in intra-regional trade. Intra-regional exports in 2021 amounted only to 13% of Latin America’s total exports, down from 21% in 2008. For instance, the Chinese strategy has fuelled tensions between members of the regional organisation MERCOSUL. Rather than seeing it as a regional group, Beijing looks at MERCOSUL countries individually, pushing Latin American countries towards bilateral ties and discouraging a common regional agenda on external relations.

The left is back, but is regionalism too?

In conclusion, the current conjunction of international and domestic factors does not augur well for a big comeback of regional projects by this new Pink Tide. With the aftermath of COVID-19 and the global economic crisis hitting Latin American countries particularly hard, leaders are more concerned with staying afloat domestically. Ad hoc cooperation in specific thematic areas such as climate change exists; notwithstanding, commitment to regional institutions is limited. Furthermore, China’s growing protagonism in the region has slowed down intra-regional initiatives. Political divisions within the Pink Tide are also surfacing, causing disturbance and obstacles for regionalism. In this sense, attempts to revive UNASUL and turn it into an effective organisation will face an uphill struggle and will require more than political declarations.