The European Investment Policy after the CETA Opinion

The European Court of Justice (ECJ) this week rendered its long-awaited Advisory Opinion 1/17. The ECJ considered that the mechanism for the settlement of investment disputes in the Comprehensive and Economic Trade Agreement (CETA) is compatible with the EU treaties.

___________________________________________________________________________

Investor-State Dispute Settlement: A Controversial Mechanism

International investment law, the branch of public international law that regulates foreign investment, features an interesting interplay of bilateral, regional and multilateral approaches. The main sources of investment law can still be found at the state-level, almost all states in the world having concluded one or more bilateral investment treaties (BITs). Of the several thousand BITs that have been concluded over the past seven decades, EU member states concluded some 1200 BITs with non-EU states. But the investment treaty regime has been in flux over the past decade. For example, regionalism in international investment law has been on the rise. In the European Union, the Lisbon Treaty brought foreign direct investment under the EU’s exclusive competence for the common commercial policy. Over the past few years, the EU has quickly moved to develop its own investment policy. A major part of this policy relates to the EU’s proposed reform of investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS). The controversial mechanism allows investors, in specified circumstances, to sue a state before international arbitral tribunals. Historically, states have primarily given “advance consent” for such arbitration in their BITs. As a result of protests by several European civil society groups against ISDS, the EU has moved to reform ISDS. The EU’s first move has been to replace the classical ISDS mechanism with a more court-like, institutionalized “Investment Court System” (ICS) in its trade deals, such as CETA with Canada, which includes a CETA Tribunal and Appellate Tribunal. The EU’s long term goal however, is to come to a multilateral reform of ISDS, by the establishment of a Multilateral Investment Court. Talks about the reform of ISDS are currently ongoing at the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL), with the latest meeting having been held in April 2019. However, true multilateral success for investment law has been limited. Though most countries in the world are now party to the ICSID Convention (an international arbitration institution in Washington DC), attempts to come to a multilateral treaty on investment have consistently failed over the past century.

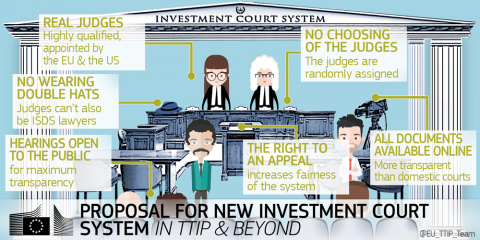

Image 1: The EU’s Investment Court System as proposed by the European Commission in 2015

ICS gets a green light from the ECJ

On April 30, the EU’s ICS was scrutinized by the European Court of Justice in a highly anticipated opinion. As a result of opposition to CETA by several regional governments in Belgium, Belgium had asked the ECJ to issue an advisory opinion on the compatibility of the ICS system with the EU Treaties. The ECJ has a legacy of safeguarding the EU “autonomous legal order” (the principle is difficult to easily explain, but embodies the idea of EU law as an independent source of law, with the ECJ being the final authority on the interpretation of EU law). The ECJ had been fairly skeptical in the past of the establishment of international courts that could issue decisions against the EU or its member states, and which it believes could in certain cases curtail this autonomous EU legal order. However, the ECJ this week sided with the arguments made in favor of ICS, holding that the relevant section of CETA is compatible with EU primary law. Focusing on the autonomy argument, the Court noted that CETA tribunals could only apply the provisions of the relevant CETA sections. Secondly and more controversially, the ECJ also gave a positive nod towards the host of conditions in CETA, which were drafted by the parties to better confirm the right to regulate and protect public interests. This is relevant, because whilst CETA tribunals cannot determine the legality of a measure of secondary EU law (for example, a new regulation that imposes certain costs upon companies for the purpose of environmental protection), they can decide whether such measures are a breach of the relevant provisions of CETA (for example, a breach of fair and equitable treatment). The ECJ held however that CETA provides enough safeguards, stating that the “Parties have taken care to ensure that [the CETA Tribunal and Appellate Tribunal] have no jurisdiction to call into question the choices democratically made within a Party relating to, inter alia, [public order, public safety, protection of health and life of humans and animals, amongst others]”. At the same time, the ECJ also held ICS compatible with the principle of equal treatment and effectiveness, as well as the right of access to an independent tribunal.

Video: the EU and Canada trade deal – CETA: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xbKOvxIYpDc

Important consequences, but an uncertain future

Image 2: ISDS reform is currently being discussed at UNCITRAL (source: SOMO)

The Opinion has major consequences for the EU’s investment policy. On the member-state level, the ratification of CETA can now continue (the majority of the treaty had provisionally entered into force in September 2017, with apparent early positive results). However, ISDS has now simply become a political issue again, and member states might continue to object to its inclusion in EU-trade deals. Likewise, the CETA Opinion might have other consequences. Whilst the European Commission’s DG Trade nowadays negotiates free trade agreements with investment protections, as well as standalone BITs, member states can still ask authorization to amend or conclude BITs of their own accord in certain cases (for example, see the recent new Model BIT of the Netherlands and the proposed new model of Belgium and Luxemburg). The high bar set by the ECJ, when it comes to the “level of protection of a public interest”, might now also be asked by the European Commission of its member-states when they ask permission to negotiate BITs that include ISDS (as noted by the UN Conference on Trade and Development before, many older BITs need to be urgently modernized). Secondly, the decision is important for the European Union itself. A red card for ICS would have forced the EU to go back to the negotiating table with Canada, and might have spelled an end to the inclusion of any kind of ISDS in EU trade deals. Finally, the decision is also important for the international dynamics of ISDS reform. By endorsing ICS, the ECJ has also shown that it is potentially open to a Multilateral Investment Court, and the EU can continue on its current track in the UNCITRAL deliberations.

However, whilst the ECJ has today clarified the legal boundaries of ISDS mechanisms under EU law, the political discussion concerning ISDS is bound to remain. For example, some civil society actors and countries have called for the UNCITRAL debate to go beyond ISDS and also discuss a broader, substantive rethink of investment law. Likewise, following older critics, countries such as New Zealand have recently been more critical of ISDS, and the new USMCA trade deal has likewise curtailed ISDS. Even after today’s decision, the future of ISDS thus remains unsure.